At the Review, we’ve spoken to some inspiring leaders when it comes to product design in tech. There’s Facebook’s Julie Zhou, Airbnb’s Alex Schleifer and Uber’s Didier Hilhorst, to name a few. We’d guess you’ve experienced the result of at least one of their design choices — but how to build and lead the type of design team that fuels such broadly-experienced products?

There appears to be a lot of variation when it comes to when product design teams start and with whom. For instance, Genius didn’t have a designer anywhere near the product when it was first built. But Pocket’s second hire was a designer, who made her mark on the product from the start. Some designers, like Caitlin Kalinowski, have over a decade of design experience at places like Apple, Facebook and Oculus. But others have designers who come from a variety of professional backgrounds: Airbnb counts a former librarian, mechanic, therapist and modern dancer on its design team.

So where’s an early-stage startup to begin? What follows are the key pieces of advice related to building and leading product design teams that we've published over the years. We hope they'll come in handy for you, whether you’re a startup’s sole designer or guiding a design organization of hundreds.

Don’t be the smartest — and only — person in the room.

It’s hard to imagine Jeffrey Kalmikoff being intimidated by anything. Before his role as product designer at Uber, he was the Head of Design at Betable, both the technology VP and only designer at location startup SimpleGeo, single-handedly ran design and UX at Digg, and spent seven years as Chief Creative Officer at Threadless. Kalmikoff’s an expert at autonomous creativity – and his advice may help those who find themselves as their startup’s only designer.

His most important tip? Don’t fool yourself into thinking that all the best ideas are yours. No matter how good you are, if you design in a vacuum, you’re going to a) burn out immediately, and b) end up with a pretty bad product. So leave your silo and tap into the people around you.

That can be easier said than done, as one of the biggest challenges a designer faces is context switching. It’s also where one loses the most time — a resource you especially can’t waste as the sole designer. “We’d all like to think we’re multi-taskers, but the fact of the matter is it takes time to wind up on a project, switch to something else, wind back down, and then jump back into something else,” Kalmikoff says. “You look back at your week and see how much time you wasted just by trying to be productive. It’s pretty sad.” Distribute your brainstorming power — you can have your idea engine running the whole time and lose less ground.

Find candidates as a fan. Interview their work.

Julie Zhuo started working at Facebook over a decade ago at age 22. Today, as VP of Product Design, she feels like she was able to grow up with the organization — and as a result, shape several of the processes that have made Facebook unique. One of these defining processes is hiring some of the best design talent in the world to think through the complex and often delicate interactions people have online. And Zhuo has seen both sides of the coin: How to hire designers for a mature corporation, and what to look for at the very beginning.

In reflecting how Zhuo hired some of their early designers she recommends sourcing lists of beloved apps and products from your whole team — not just the ones that are commercially successful, but even small apps or ideas that have an angle of something great, selecting for the ones that showcase the same skills and interactions you’re looking to build. “Read the small print on products with elements you like — like a particularly effective UX, or an innovative feature, or a very polished, well-done navigation system, and then hunt through Google, LinkedIn and AngelList until you find the people behind them.” After you do that, don’t be too shy to reach out. People love hearing from fans, no matter what kind of work they do.

Once they’re in the pipeline, get to know them, but even more so “interview” their work. It’s critical that your hiring team scrutinizes the apps, websites or products that designers have built as part of their portfolio or previous work experience. Both the candidate and the work should be able to withstand it. To make sure they’ve taken a thorough look, Zhuo provides a checklist to her hiring teams to analyze the quality of the work presented:

- The idea: “Is there a solid rationale behind why they worked on what they worked on? Does it identify a real problem and attempt to solve it?”

- Usability: “Is it easy to use? Is the design thoughtful and clear for how this product works? Does the designer have a good grasp of common patterns and interactions?”

- Craftsmanship: “Did the designer sweat over all the details, both big and small, of the end-to-end product? Is there a sense that the final product is well-made? We’re not looking for something that’s just functional. We want products that leave people feeling like the folks who built this cared about them and their individual experiences. That aspect of high quality and craft is extremely important to us.”

It's impossible to talk about design without looking at the work.

Fuse Engineering, Product and Design from the start.

To the solo designer who adds a partner, then a third colleague and so on, don’t return to your silo now that you’ve got design brethren. Alex Schleifer, VP of Design at Airbnb, recommends laying groundwork to build toward an EPD — engineering, product and design — team from the beginning. Some tech companies have adopted this approach to increase the involvement and alignment of each function from a product’s inception to its launch.

For example, a working group for a new feature, product marketing or user feedback will involve at least one member from each of the three teams. This coalition not only assembles the key builders of the product, but, as a byproduct, it also formalizes the professional pathways — in product, eng and design — that a person who wants to continue creating products can consider.

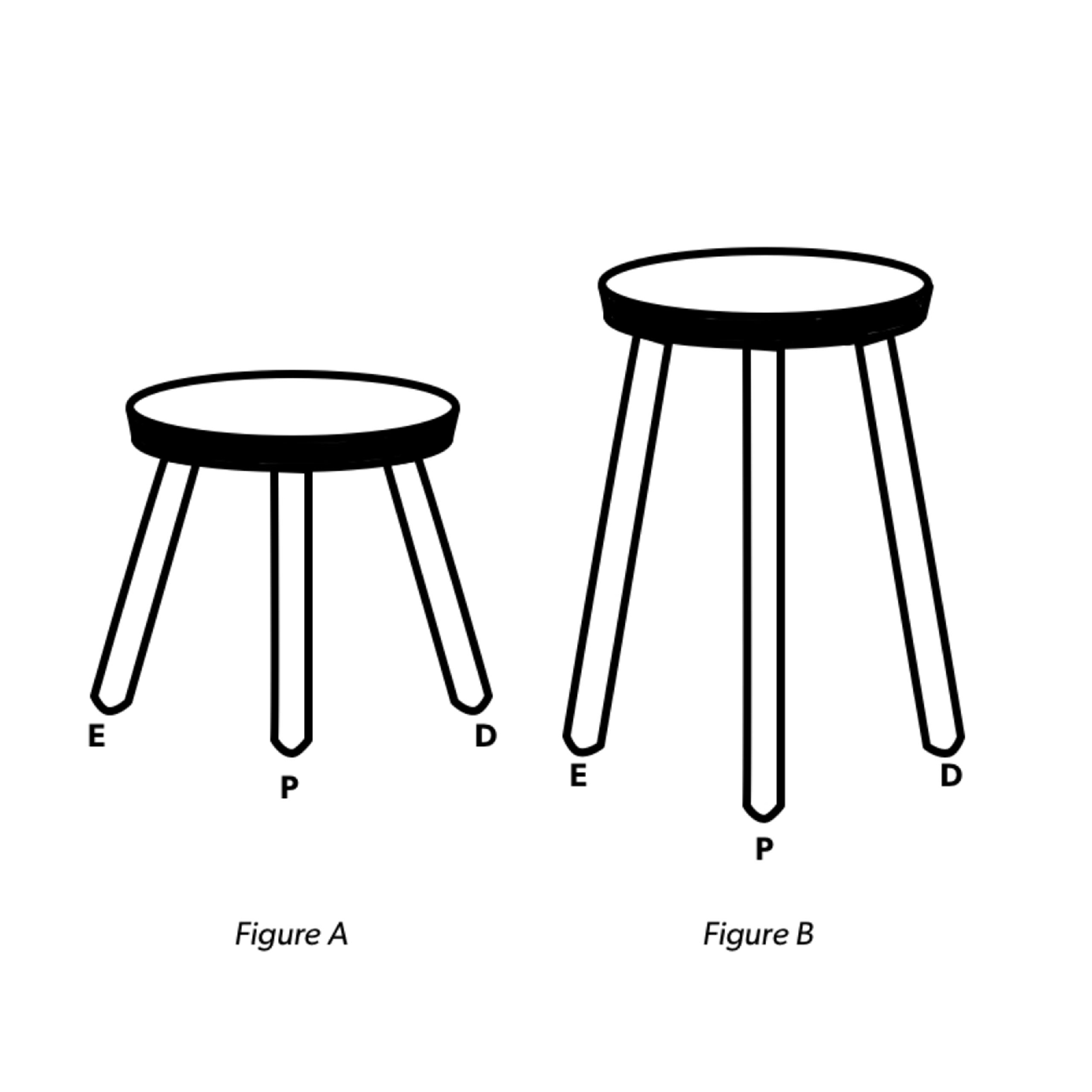

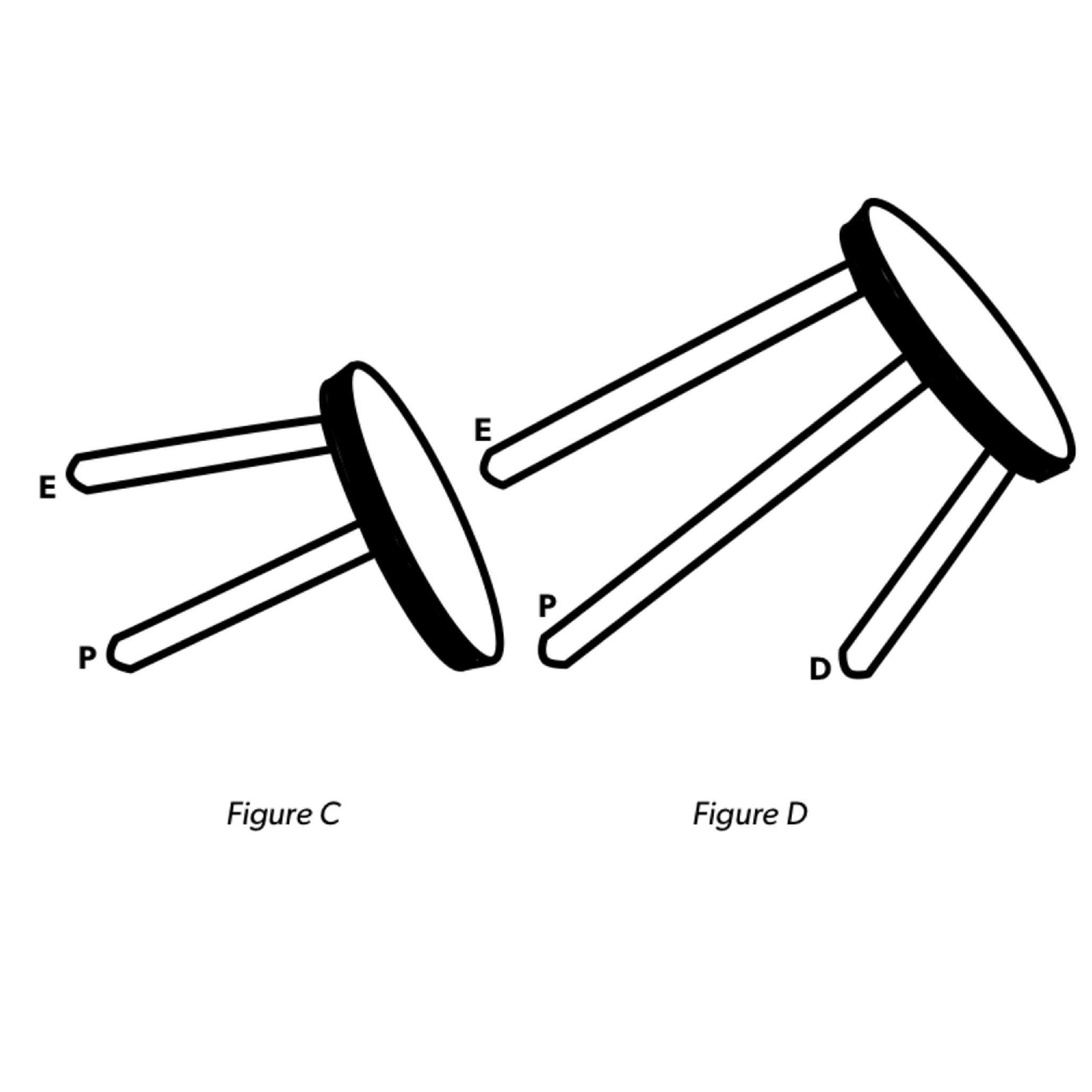

To put a fine point on it, the team should resemble a three-legged stool, in which each leg represents one of the three areas that helps build a product. If it’s done from the start (Figure A), each function can grow in parallel and at the proper ratio (Figure B) as the company grows.

Without those strategies from the onset, you’re bound to create an unstable stool down the line, which, in this case, can lead to a shaky product. That might be because no design role was developed at the onset (Figure C) or was added on after the product — and the eng and product management teams — has already matured and grown (Figure D).

Let designers own their best-case scenario.

Caitlin Kalinowski has a keen mind for design, especially as a master of the prototyping process. She has a deep understanding of where, when and how changes should be slotted in, from the first iteration to the last. It’s made her a highly sought-after product design engineer in Silicon Valley. Before her work as product design engineering director at Oculus, she was the technical lead for Apple’s MacBook Air and Mac Pro. She also led and shipped Facebook’s Bluetooth Beacons, which power location-based prompts for users.

As your design organization grows, its different functional areas will inevitably be at odds. Here’s what Kalinowski recommends doing: let each team own their best-case scenario.

When developing Apple’s cylindrical computer, the Mac Pro, Kalinowski had to juggle a multitude of perspectives. “The industrial design team wanted the device to have a really small diameter. But that meant a small diameter on the heat sink... When the heat sink was small, more air had to be pulled through to cool the central processing unit (CPU), making it louder. Yet still we needed the computer to be quiet,” Kalinowski says. “The way to solve this problem was to let each team completely own its best-case scenario. There were separate teams inside Apple focused on optimizing for small diameter, focusing on keeping the noise down, worrying about the heat transfer — we just let each one own that and drive as hard for their goal as they possibly could. For the thermal team, since this is a high performance machine, we needed the CPU performance as unlocked as possible, and so we let them fight for that. Then the audio team made sure the fan noise didn’t cross a certain threshold. Let everyone work on the best possible outcome for the feature for which they’re responsible, and you’re likely to end up making the best product trade-offs — and that means a better product."

Encourage stupid side projects — welcome them into your teams.

Former Spotify Product Design Lead Tobias van Schneider is a fan of side projects — but they must be stupid. “The only way a side project will work is if people give themselves permission to think simple, to change their minds, to fail — basically, to not take them too seriously,” says van Schneider. “When you treat something like it’s stupid, you have fun with it, you don’t put too much structure around it. You can enjoy different types of success.”

But side projects have institutional effects — especially for its creatives and designers. The best thing a startup can do to maintain its creative edge and keep its most talented employees invested in the company is make time and space for stupid side projects, van Schneider says. While larger companies like Google and Apple can build this into people's jobs on a regular basis, more and more startups are providing time in the form of hack weeks and hack days. “Companies underestimate how important it is to give employees the time and space to listen to their hearts and explore the things they are interested in,” he says. “This is something that is impossible to measure — which turns a lot of people off in this very data-driven business.”

Running hackathons so your designers can pursue side projects may not be enough. People will see that their company has invested in developing employee ideas and they won’t be able to wait for the next hackathon to roll around. “When you have this kind of energy, you want to tell people that they don’t have to wait for the next hack day opportunity. Give them permission to take one or two hours out of every day where you’re paying them to innovate and pursue things they want to do,” says van Schneider. “Build in ways for people to share this kind of work with their peers and their managers. Make them feel rewarded or you risk losing them.”

If people find the time and have great ideas, they will do it anyway. They will be gone.

Clear paths for generalist designers to become design leaders.

Phil King has spent nearly two decades in product design, much of it in leadership positions. Earlier in his career, he moved up the ranks at eBay before taking the reins as Director of User Experience and Design at Flickr. More recently he’s held the lead product design role at Bebop.co (acquired by Google), Nextdoor.com and Udemy.

One of the most notable inflection points in his career happened just as he joined eBay, after several years designing at startups. Within the first 18 months at eBay, he evolved from an individual contributor with an interest in interaction design into management. He learned that larger companies like eBay had a culture that encouraged specialization. Interaction designers focused on how things worked. Visual designers focused on how things looked. It was a hard environment to be a generalist, but it’s one of the qualities that drew King into a leadership role.

He worked to bring the specialists on his team at eBay together as a group, helping project teams form, understand, and solve design problems seamlessly. The bottom line for product design leaders? Growing skills as a generalist designer, and especially seeking ways to use broad design thinking to support your team are key steps to operating as a designer at the leadership level. Offer these opportunities to your team. “I think my background as a generalist designer, combined with time spent focused on interaction design, helps me see products and design challenges more holistically,” he says. “The ability to build empathy, connect the dots on complex problems, and help teams apply design thinking are crucial skills a designer can bring to a leadership team.”

This is just the beginning of the Review's wisdom on design. Check out the full articles referenced above in our Design magazine, as well as others on how to design products to eliminate cognitive overhead, how to run effective design critiques, and how to approach and execute a product redesign.

Photo by Thomas Barwick/Stone/Getty Images.