This article is by Sunita Mohanty, who is a Product Lead as a part of Facebook's New Product Experimentation. She has built products for startups, nonprofits and global public companies, most recently leading product teams at Oculus, Facebook Core Growth and as Director of Product at Lumosity. She is also a startup advisor, angel investor, and member of First Round’s Angel Track community.

In my role leading product teams as a part of Facebook's New Product Experimentation, we’re focused on that hazy “0 to 1” stage of building, where ideas are unproven and products are in their most nascent stages. My job is to distill the complicated unknowns of a big, disruptive vision into clear, actionable steps for my teams and increase our chances of finding product-market fit at every step. This focus on taking big swings while still pursuing concrete steps toward building valuable products is the direct result of my previous experiences — I’ve felt the pain that comes from building products that fail to tackle a clear problem firsthand.

Right after grad school at Stanford, I found myself in the middle of my first startup: a failing K-12 analytics company. We were on a mission to improve a broken education system with the promise of interesting technology. But we were stuck in circles of decision-making and couldn’t successfully execute or build traction. Looking back, it’s easy to diagnose that we had a hard time focusing on which problem to solve first because we didn’t understand the actual problems of our audience well enough — we only assumed we did.

Now in my work as an angel investor and advisor, I see teams run into this very same brick wall. As I help them prioritize early product and go-to-market efforts, I often find myself dishing out the same advice: Do the work to make sure you are building a product that people will actually find valuable. That requires an incredibly deep understanding of the user, their hopes, and their motivations, instead of taking the easier path of operating off of untested assumptions.

Many entrepreneurs may do this intuitively — but many others fail to cultivate a deep level of empathy for their users, which ultimately can lead to building the wrong product for any specific market. If you don't put in the work upfront, you risk charting the wrong course towards product-market fit, which you may not discover until you’re facing struggling retention numbers or battling high user churn.

There’s a range of philosophies out there on how to avoid this trap and better approach early stage customer development, but in both my advisory roles and in my day job, I've come to rely on one framework: JTBD (jobs-to-be-done).

I first read Clayton Christensen’s approach to JTBD while in grad school at Stanford, but it didn’t really sink in. After stumbling upon it again years later at Facebook, I’ve since found enormous value in employing a version of this framework as we built Oculus social features, Facebook Preventive Health, and more recently, Tuned.

JTBD is by no means a new way of thinking. But it can be confusing to get started with, since it’s heavy on the corporate strategy jargon and has been reinvented many times over. A quick Google search reveals a bevy of confusing terms, from the debate over jobs-as-progress and jobs-as-activities, or the competing visualizations of maps and hierarchies. I’ve also found that JTBD has a bit of a consulting-esque vibe and seems less vision-driven, which can be off-putting to many product-driven founders.

If you’re looking for a deep-dive into the jobs-to-be-done theory and how others apply it, I recommend reading through this primer from The Christensen Institute, this article from Harvard Business Review, Alan Klement’s overview of two different interpretations and Intercom’s guide. But if you’re looking for something a bit more lightweight and accessible for startup product teams, read on for my simplified approach to JTBD.

In this article, I’ll detail the version of this framework that’s used by product leaders at Instagram and Facebook, and applied in my capacity as an angel investor and advisor to early-stage teams. I’ll walk you through my template, examples from other companies for inspiration, and advice for the entire process from early concepting to launching and refining. In addition to outlining the case for using a framework instead of relying only on your gut, I’ll share tactics and templates for pulling together a clear set of product development principles that can inform your value props, PRDs and go-to-market tactics in order to execute with precision.

WHY YOU CAN’T JUST WING IT: THE CASE FOR USING A FRAMEWORK TO UNDERSTAND YOUR CUSTOMERS

Do you find your team is unable to align on what matters most about your product as you’re starting out? Or that you’ve worked hard to bring something to market that you were all excited by, but you’re not getting traction with users? Founders, early-stage teams, and even later-stage product orgs run into these problems time and time again. The bottom line is that you can very easily build something, but to increase your chance of creating something that is solving a real problem you need to be more rigorous in your approach.

Anyone can build products. Not everyone can build products that solve a real problem and land product-market fit.

More specifically, here are three common problems I see both early- and late-stage product teams running into that indicate a framework might be useful:

- 1. You’re relying too heavily on your own vision. You’re not really listening to your users and you’re building something you think people want. This is confirmation bias at play — the human tendency to cherry-pick information that aligns with our pre-existing beliefs while ignoring information that doesn’t. If you haven’t gotten out and deeply understood who you are building for and what problems they experience, you are more likely to run into this problem. Another variation happens when translating research-based practices into consumer experiences (common in health and education products) — just because something is proven to be healthy or lead to good outcomes doesn’t ensure people will be motivated to try it out.

- 2. You’re more focused on the excitement of the technical challenge than your users. Often, eng and design teams may get excited about a specific project because it’s a new challenge to create. But just because it’s new and fun to build doesn’t mean people will actually use it. This tends to be one of the more common pitfalls of hardware teams, which have an especially high cost to getting their products wrong.

- 3. You can’t crisply articulate your value prop, and everyone on the team looks at it a different way. We’ve all been there — product sees the value as X, marketing sees the value as Y, eng sees the value as Z. This happens when you don’t have a shared sense of empathy around the problems users face. It makes it tough to drive alignment and focus on what features matter the most or how to align product features with go-to-market needs.

Intuition and conviction are extremely important in building early-stage products, but pairing it with listening to users can increase your chances of being right.

ENTER THE JOBS TO BE DONE FRAMEWORK: WHAT IT IS AND HOW IT TAPS INTO WHAT CUSTOMERS WANT

Whether you’re a product manager innovating within a larger company, or building a brand new early-stage product at a startup, the JTBD framework works to create better, non-obvious insights about your audience. Ultimately, the core value of this framework is that it provides an approach to gathering an understanding of who your user is, and what their motivations and hopes are. You as the founder or product leader are left to determine how to translate this into what matters most for your product — combining great intuition with great information gathering to make better bets on where to invest resources.

While JTBD has been used for 30 years in industries making physical goods, it’s relatively newer in software building circles. The theory of jobs to be done centers around understanding customer behavior and underlying rationale for making choices.

The idea is that innovators win by resolving a consumer’s struggle and satisfying their unmet aspiration. Harvard Business School marketing professor Theodore Levitt explained it this way: "People don't want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!” When describing his now classic milkshake example, Clayton Christensen summed it up this way:

"People don't simply buy products or services, they 'hire' them to make progress in specific circumstances."

In this theory, people are trying to complete certain “jobs,” which they in turn “hire” a specific product or service to help them accomplish. They may “fire” a product or service if it is not adequately completing the job.

BUILDING BETTER PRODUCTS STARTS WITH A GOOD JTBD STATEMENT — HERE’S YOUR ROADMAP

A jobs to be done statement concisely describes the way a particular product or service fits into a person's life to help them achieve a particular task, goal, or outcome that was previously unachievable. When crafted well, these statements create clarity around what doesn’t exist today and what product builders can focus on to innovate. In my experience, the exercise of creating a clear JTBD statement is the most important part of this framework. In this section, I’ll walk through why you need one, offer both advice and my go-to template for putting your own statement together, and share example statements from several companies as inspiration.

Why you need one:

A good, crisp JTBD statement captures underlying motivations, triggers and context for the problems your user faces. This statement can be foundational for your entire product and GTM planning, from focusing your PRD or product spec, to identifying your channels and marketing messages.

A good statement will help remove bias, build empathy for users and bring alignment across product, marketing and eng teams. When you have a well-crafted (and well-communicated) jobs to be done statement, the following things start to fall in place:

- An increased focus across your team on solving the most important problems by using shared language for how you all understand what problems to prioritize

- A higher likelihood of delivering new value to people by solving real problems, which should translate into positive leading indicators of important product metrics (like higher engagement and stickiness of your product)

- A stronger understanding of competition for your product, by understanding more about the situational context and full set of alternatives that people “hire” to do that job.

Here’s an example of the power of the JTBD statement in action: Recently, one of the startups I angel invested in reframed their early product thinking using the JTBD framework. As a team of two engineers, they found themselves thinking along the lines of very specific user stories based on the broad goal of their product for remote teams. After re-thinking their approach to customer interviews using JTBD and arriving on a clear statement based on what they heard, this team was able to re-frame their product to focus on encouraging fun — and found promising early traction with this new value prop.

Put in the legwork: A template and 4-step process for crafting a standout JTBD statement

Before putting pen to paper, lean on these guidelines:

- Jobs are not the same as your mission, vision or goals.

- Jobs describe the underlying human needs, not the features of the product.

- Jobs illuminate consumer insights on underlying motivations and struggles, not business objectives.

- Importantly, a job should highlight a promising specific market opportunity about an unmet need — balancing between too broad or too niche. What exactly is too broad or too niche? This is more art than science, but as Paul Graham describes: “You can either build something a large number of people want a small amount, or something a small number of people want a large amount. Choose the latter.”

A clear JTBD statement should help you communicate with absolute clarity what a specific group of people want in a specific circumstance — and their barriers to getting it.

The basic jobs-to-be-done statement framework is specific about the context people are in today, the barriers in the way of achieving their goals, the goals they want to achieve and their desired outcome.

To put that into practice, here’s a JBTD statement template that I find helpful and is commonly used amongst Facebook and Instagram product teams:

- When I…… (context)

- But…… (barrier)

- Help me…. (goal)

- So I….. (outcome)

With those principles and end goal in the background, follow these four steps to gather all the info you’ll need to fill out your JTBD template:

1. Start by defining your audience clearly.

Think about the defining characteristics that help you develop a crystal-clear image in your head of your audience. Without a clear definition, you risk going too broad or gathering signal from the wrong kinds of people.

2. Ground yourself in market research.

Understand as much as possible about this audience’s behavior: what they currently are using to solve this specific problem and where they feel the most pain in the customer experience. Test out all the products related to what you’re building or what users have hacked together to accomplish the job. You should arrive at a clear understanding of the alternate products they are “hiring” or “firing” to accomplish the job and why.

3. Talk to your users.

Using surveys and interviews, get a firsthand account about your user’s mindset and decision process (related to what you are building). More specifically, try to:

- Understand the underlying motivation and context: What do they hope to do? Emotionally and functionally? Where were they and what is going on around them situationally?

- Understand barriers and struggles: What prevents them from getting this done?

- Understand what they are currently “hiring” and “firing”: What are they currently doing, or hacking together to get the job done? What do they not use because it doesn’t get the job done?

Whether you’re using surveys or interviews, carefully word questions so that you are not leading people to a specific answer. For example, when we started concepting Tuned, we began by doing research into couples’ general communication patterns before asking specifically about apps for couples or the solutions we were thinking about. The problems we heard from these conversations helped us to prioritize amongst a range of ideas to focus on emotional connection over tactical task management, like keeping track of grocery lists.

Stepping back to understand deeper context and underlying motivation is important because people are notoriously bad at predicting what they want.

4. Prioritize.

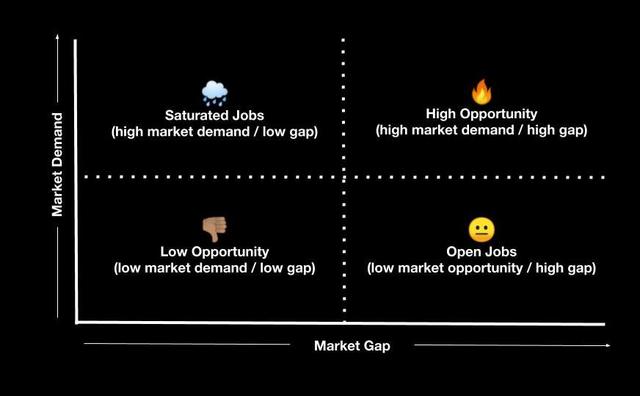

There are many customer jobs your product could tackle, but focus is paramount here. From user interviews, look for themes that emerge in jobs to be done. You can also run surveys that ask users to rank the importance of jobs and how well each job currently is served by another app or product to gain a better understanding of the market opportunity. This can help you to narrow down jobs and prioritize those with the most demand and the largest gap to be filled.

I like to use this framework when thinking about which jobs to tackle:

If you can, try to go through the steps above to develop a first pass at a JTBD statement, and then retest it using surveys or interviews, asking users questions to find out if this job matters most to them in order to tighten your JTBD definition. Taking in new information to refine your JTBD allows you to re-examine your core assumptions and update your own intuition.

JTBDs IRL: Examples to bring this framework to life

To take it from the realm of theory to the more practical, let’s unpack some different products (some I’ve worked on and my analysis of others), their audiences and their JTBDs. These aren’t the case studies you’d encounter in business school, but rather quick real-world examples (from companies I respect and my own team) that might help guide your own thinking.

Discord:

- Core audience: initially PC gamers

- Motivations: communicate synchronously while playing a game, find others and organize enough people to get a game going

- Barriers: split attention while playing a game makes it hard to use chat only, connecting with others who share your gaming interests and skill level

- What else are they hiring/firing: other social media, messaging apps

Discord JTBD: When I want to jump into my favorite game, but I don’t know if there are people around to play, help me safely coordinate with a group of like-minded gamers, so I can easily find a way to enjoy my favorite multiplayer game. This suggests features like making it easy to find people through public or private servers and switching easily from text to voice chat as you organize and jump into a game.

Peloton:

- Core audience: upscale, fitness oriented super moms (or dads)

- Motivations: Working out to staying healthy (feeling good and staying sane), working out as a social experience, quick but efficient exercise, variety and accountability

- Barriers: Difficult to go to the gym or to classes (because of kids)

- What else are they hiring/firing: Gyms or studios, other home gym equipment, outdoor exercise

Peloton JTBD: When I need an option to workout, but I can’t go to my favorite studio, help me to get a convenient and inspiring indoor workout, so I can feel my best for myself and my family. This suggests features like an instructor-led experience, light social motivation through leaderboards and high fives and, most importantly, a physical bike are important core parts of the value.

Segment:

- Core audience: startup developers and/or consumers of marketing/product analytics

- Motivations: making faster and better informed business decisions using a full picture of analytics on customer behavior

- Barriers: extremely laborious and highly error prone to access a full picture of customer data because it is collected across many interactions and sources

- What else are they hiring/firing: separate data sources with bespoke integrations, existing ETL pipelines, other customer analytics platforms

Segment JTBD: When I need to understand what people are doing on my platform, but I have different sources of data that all tell me different stories, help me easily pull together one source of truth so that I can make better product and marketing decisions to improve my business. This makes clear the core value of Segment’s single API that allows companies to tap into dozens of analytics services to create a single view of a customer.

Mutiny:

- Core audience: Account Based Marketers at B2B companies (note, this is only one persona out of the several that Mutiny considers as it’s core audience)

- Motivations: accelerate sales by helping high value enterprise accounts understand and trust their company’s value

- Barriers: limited time and resources, unsure what strategy will yield the best results

- What else are they hiring/firing: ABM advertising platforms, online event software, email marketing

Mutiny JTBD: When I need help enterprise accounts discover and trust our value prop, but I have limited time and resources to test different approaches that might resonate, help me quickly and confidently deliver the right message. This makes clear how Mutiny conveys its value prop — rather than focusing on its capabilities as a personalization platform, it suggests emphasizing ease of use and ROI when ABMs use their platform.

Tuned:

- Core audience: Millennial couples, together for >6 months

- Motivations: having a private space for their relationship, wanting to express themselves more fully to a partner, celebrating memories together

- Barriers: Restricted emotional range and miscommunication via digital tools

- What else are they hiring/firing: other digital communication tools

Tuned JTBD: When I want to feel connected to my partner, but don’t have a special way to share my feelings, help me be more emotionally expressive, so we can strengthen our bond. This suggests a set of features that give you a wider emotional range (like sharing your mood, stickers, greeting cards) to feel a moment of deeper connection with your partner vs. tactical features like keeping track of grocery lists.

NOW WHAT? HOW STARTUPS CAN PUT JTBD INTO PRACTICE

JTBD isn’t a static statement, nor is it a one-time exercise suited for the entirety of a company’s lifespan. I see teams often go through this process once, but then fail to revisit this with new information as they execute. This is a framework to be regularly updated, and it’s relevant across all stages and challenges that product teams encounter. If used well, it can continually focus on what matters most as a north star and increase the odds of finding product-market fit.

How to incorporate JTBD into the product org:

Beyond the value of clearly capturing JTBD in the early days, you can weave it throughout your product team’s process as you start to spell out your value props, PRDs and go-to-market tactics. Through each step of planning to execution, JTBD can provide the clear set of principles that drive the hypothesis you are trying to prove of what brings value to users.

See below for some more specific ideas of how you can weave the JTBD framework into each stage of product development — and check out the templates I’ve come to lean on in my own role.

- 1. Idea generation: Turn JTBD into “How Might We” statements, helping you crisply articulate the problems that your product should solve. For example, with Tuned, we wanted to solve for the job of helping people be more expressive with their partner based on jobs that we heard were most important. We guided our brainstorm with the statement “How might we help couples express a broader range of emotions with each other more easily?”. This led us to develop the mood feature, where partners can select a mood and color to show how they are feeling.

- 2. Feature prioritization: Based on JTBD statements, run a brainstorm to generate possible features that address this specific value prop. If you have multiple important JTBDs, consider picking one to prioritize as a theme of features for a specific interval in your roadmap, such as a sprint or a quarter. For example, when building the first version of messaging in Oculus, we prioritized features that allowed people to coordinate play in VR over features around expressiveness. We did this because we knew it was important to solve for reducing the barrier to get into VR with another person through initial JTBD research.

- 3. Value prop testing: From your JTBD statements, narrow it down to two or three value propositions that emerge as most important to your audience. A strong value prop conveys what is specific about your product and brand that compels people to take action. Run a “Fake Door” test (using Facebook or Instagram ads, Google Ads and/or App Store tests) before you even build anything to quickly validate what resonates the most with your audience — without eng resources.

- 4. Go-to-market planning: You might have a dedicated marketing team, or you might not yet be there — either way, you can work from the JTBD statements and winning value props to identify your distribution strategy, craft your key product marketing messages, and brand positioning. Once you determine the timing and goals of your GTM, you can identify the key channels you’ll leverage. Depending on what channels you use, you can weave in your understanding of emotional and functional appeal from your JTBD to create marketing copy and content like landing pages, AdWords campaigns and Facebook or Instagram ads. For more depth on go-to-market, read more on how to “pick the right lane for customer acquisition” or check out this great breakdown of 10 companies GTM strategies.

- 5. Analyzing customer data and feedback: Once you are live to users, you are on your path to product-market fit and likely will be maniacally focused on engagement metrics, retention figures, also utilizing leading indicators like the PMF Survey. Using this combination of data to understand user behavior, you can develop personas of users and validate (or invalidate) your hypothesis of how users find value in your product. Superhuman co-founder Rahul Vora shared great advice about using this in-product survey feedback “to double down on what users love and address what holds others back.” Consider augmenting this survey with a question where users can select what value prop matters most. This can help you refine your core JTBDs and hone your focus on what users love.

How to revisit your JTBD statements:

Through each of the above stages, you can come back to JTBD statements to help your product, eng, design, marketing, research and all other cross functional teams understand who you are building for and what matters most. This shared understanding makes it much easier to navigate tradeoffs — such as which features to prioritize building in your roadmap or what channels of acquisition to invest in.

Even if you’re not an early-stage product team or startup, it’s never too late to tighten up your messaging with the findings from JTBD research — or pivot to ensure you’re solving the needs that drive people to hire products. As you revisit your growth strategy, periodically do interviews to understand how your customers currently use your product. You can specifically ask people if the product is solving the job you intend it to tackle in order to validate your understanding. In the process of building Tuned, we are taking this approach to keep evolving what we know about our core audience which has led us to find more focus and opinion in our product.

Remember that this isn't a static process. The best product teams continue to refine their understanding of users and what problems are most important — improving intuition along the way.

Ultimately, building products people love requires curiosity, deep listening and truth-seeking to make sure the problems you think you should solve are truly real pain points. Taking that work on with an open mind and a systematic approach is key to instilling — and reinforcing — this mindset in your own product org.

Thank you to the First Round Review team, AJ Frank and Jaleh Rezaei for the thought partnership on this piece.

Cover image by Getty Images / Sainam Poploy / EyeEm.