When rapid growth hits, that long-awaited success can make a lot of founders long for the days when they were merely struggling for product/market fit. There are new investors and board members to court, and RSUs, MAUs and CPUs to consider. And in the onslaught of pressing demands, it’s easy to hope that employee motivation is taken care of by the company’s success alone.

Jack Chou is here with a PSA: Don’t do that.

He’s speaking from experience. Chou has been on his fair share of high-flying startups as an early product leader for LinkedIn, the Head of Product for Pinterest, and now Affirm. He’s grown a team sevenfold in 18 months, helped shape brand-new technology, and taken business lines from $0 to major money makers. He understands the chaos. But he also knows that failing to make time to learn what makes people tick (and keep ticking) can mean the difference between thriving and fizzling out.

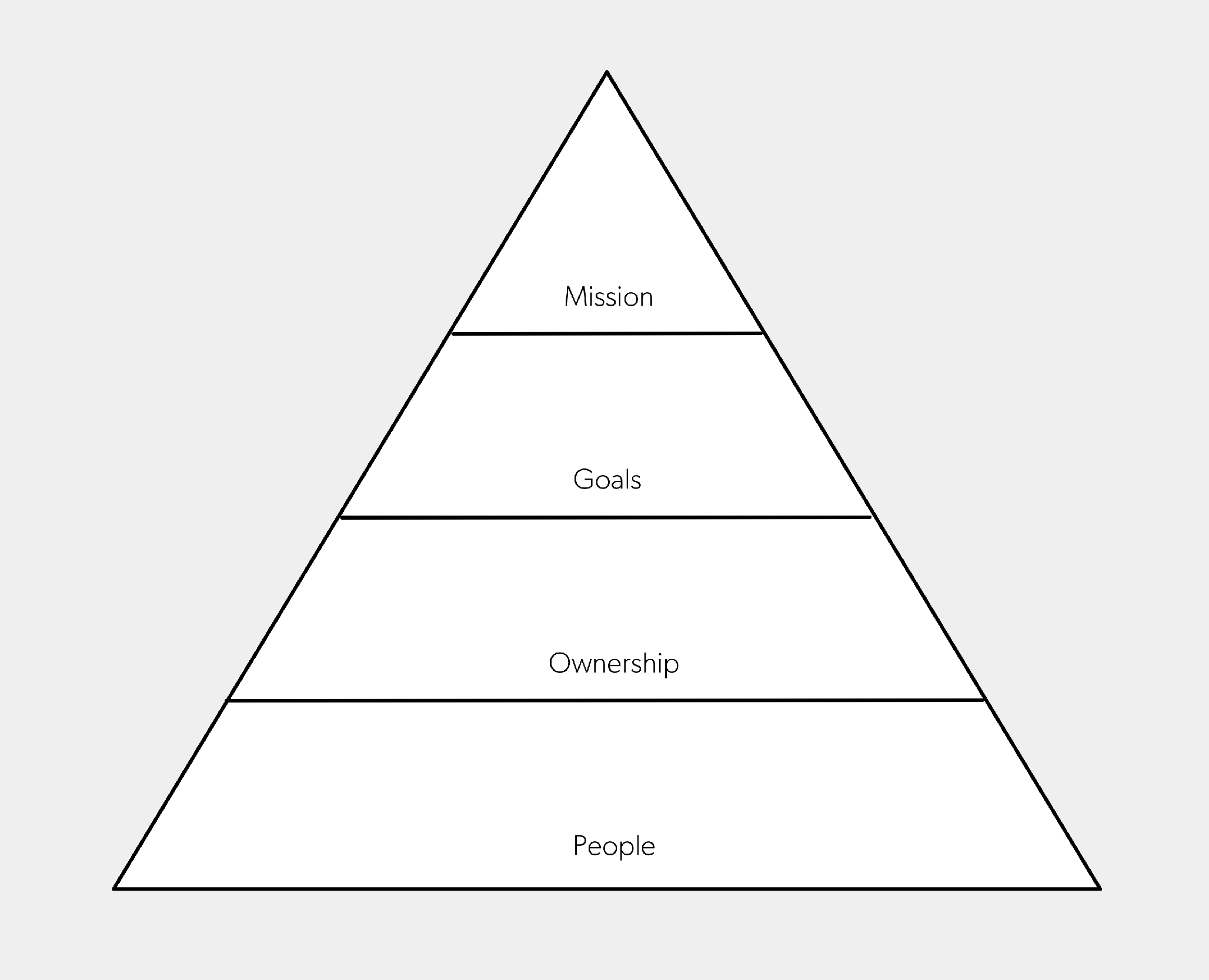

In this exclusive interview, Chou shares the pyramid he developed to explain how to build and maintain motivation—a new kind of hierarchy of needs that every startup founder and executive should internalize. He describes how leaders can spot flagging motivation in their day-to-day interactions, and offers tactics to start turning things around today.

THE ELEMENTS OF MOTIVATION

Chou identifies four key components to workplace motivation, which he visualizes as a pyramid. Each level provides the required foundation for the next; try to build on shaky ground, and your pyramid will never stand strong. And when motivation breaks down, you can always trace the cause to one (or more) of these four elements:

People

The first component of motivation is the team a person works with day in and day out. According to Chou, when team dynamics falter, it’s usually for one of two reasons.

“The first is understaffing, or a group of people that simply don’t get along. Nothing saps motivation more than feeling like you’re facing an impossible task. So when a team doesn’t have the resources—in particular, the human resources—to accomplish its goal, it’s an uphill battle to stay upbeat and focused,” says Chou. “The thing that we used to say at LinkedIn, when we were explicitly trying to solve this issue, was ‘The only thing that matters right now is getting small teams of dedicated resources. That’s it. Everything else can follow from it.”

The second cause of shaky teams is interpersonal friction, an even more pressing and often intractable problem. “If people don’t like and trust the humans they work with, none of the rest of it matters,” says Chou. “If they do — or at the very least respect the skill sets of those other folks, and are able to work with them — now we have something we can build on.”

When heads are butting early in a partnership or team dynamic, Chou recommends giving it time. In many cases, people simply need to find their rhythm. “Maybe you should be in a room for two hours just whiteboarding this stuff out a little bit more so that you can build rapport. People need the time to get past formalities,” says Chou.

Of course, in a rapid-growth environment, time is in short supply. “If somebody is new to the building and you think, ‘Oh, thank goodness that person is here to fill the role that we’ve been waiting for. We’ve got the people, now they’re just going to go,’” says Chou. “But to the extent possible, leaders should consider trust-building as mission-critical as recruiting. Put people into situations where they have to come together, think about things and design a solution together. For example, managers spend a lot of time designing starter projects for an individual. But they spend little time with their peers designing a 'starter project across teams.' Challenge your managers to create a hard, but time-bound project that crosses multiple disciplines, like design and sales. It might be a simple new feature or an intricate experiment.”

Other times, you may encounter truly irreconcilable differences. Early in a leader’s career, there may be a temptation to let it go on too long, to believe that you’ll eventually solve the problem. Chou was disabused of that notion during his time as head of product at Pinterest, when he sat down with a product leader at one of the world’s largest companies.

“I asked, ‘What's the most common team relationship issue you see?’ Before I could even finish the question, he said, ‘PM and designer.’ At the time, I was coming up against that issue all the time, too. When I asked what he did to solve it, he said, ‘I just separate them. One time in my career I was able to get a PM and designer that didn’t get along to eventually work well together. But I’ve tried hundreds of other times.’”

That veteran product leader did have a favorite trick for getting ahead of the issue: holding regular team hackathons to see which pairs naturally chose to work together.

Interpersonal dynamics are an important consideration when structuring project teams, and product and design leaders shouldn’t hesitate to candidly discuss them as they make staffing decisions. Being intentional about those dynamics is being respectful to those teammates.“I just came out of a one-on-one with our head of design, John Francis,” says Chou. “We were talking about a project that’s going to be coming up. There's a PM already assigned to it. Now who is the right designer? We talked about who the PM gets along with, and within that group, who would be a good fit for this project. Half of that fit is functional, and half of it is thinking about whether the team is going to work.”

Ownership

Once you’ve built teams that are sufficiently staffed and enjoy working together, they’re equipped to assume ownership for their work, the second component of motivation.

As a company scales, employees inevitably feel further and further away from key company decisions — literally and figuratively. “If we’re a 10-person company, I’m sitting right next to where the decision is getting made. The CEO probably sits within 10 feet of me,” says Chou. “Once rapid growth hits, you can’t keep everyone in every conversation. But every person can take responsibility for their piece of the bigger picture.”

To get there, leaders need to emphasize a culture of ownership, pushing team members to embrace their responsibility if it doesn’t happen naturally. Chou was on the receiving end of just such a nudge during a particularly memorable meeting at LinkedIn. CEO Jeff Weiner had recently come on board, and Chou found himself describing an issue to the leadership team and him. “We had a ton of ads budget that marketers wanted to spend with our fledgling Marketing Solutions business that they couldn’t. It was a big opportunity and I thought I was really smart explaining how we had this untapped runway in front of us. It never even occurred to me that it was my job to go pursue that with urgency,” says Chou. “I was nonchalant about it. ‘Yeah, this thing happened and, as a company, we’ll have to sort of it out.’”

Weiner stopped him. “He said, ‘What do you mean?’ So I said again, ‘We as a company are going to have sort it out.’ And he was just incredulous, asking, ‘Jack, do you think you’re demonstrating the proper sense of urgency right now?’ When I told him yes, he turned and asked every other person in the room whether each thought I was demonstrating the proper sense of urgency. Most of them said no. That really sears into your mind."

It also worked. Far from being dispirited, Chou left the meeting galvanized. “I thought, “This is my problem. I’ve got to figure out how to make change on it urgently. I went to talk to my teammates and said, ‘We need to solve this right now,’” says Chou. “This wasn’t a major crisis; a culture of ownership shouldn’t be about just the big moments. It’s simply a professional taking full responsibility for the next step in her business plan.”

As a leader, your job is to equip people with the right context for decision-making, then help them build the confidence to act decisively. At Affirm, for example, Chou holds product reviews a couple of times a week. “The thing I always push folks on is not to present the group two options and look for a decision. Come in saying, ‘This is what I want to do and this is why I want to do it,’” says Chou. “I recommend a similar approach to inter-team disagreements. Whenever possible, make sure that the team itself finds a solution. Don’t impose one from the outside in if you want people to act like owners.”

Leadership means clearing the path for a decision, when most people think it means making the decision. “Recently, a couple of folks came to me and Sandeep Bhandari, our chief risk officer, independently and said, ‘X person, Y person and I aren’t aligned on this topic,” says Chou. “We can't come to a verdict. Can you guys come up with a decision on this?”

Chou and Bhandari briefly put their heads together, but not to arrive at the answer — they made a quick call to ask the team to keep hashing things out themselves. “Once a team is in the habit of giving up ownership on all hard decisions, it’s difficult for them to stay motivated. So we told them, ‘Yeah, we get it. But try again,’” says Chou. “They tried again and they came up with an agreement that’s actually pretty smart, smarter than Sandeep and I could have come up with in the five minutes we spent. And they feel good about it.”

Relinquishing ownership doesn’t always mean looking for another person to make decisions, though. Sometimes it means looking for other tools to replace their own judgement. An overreliance on testing is another crutch that Chou looks out for. There’s a place for that data, of course, and a time to wield experiments and A/B testing. But Chou encourages his teams to use testing to confirm a bet—not as another way to defer decision-making.

“I always ask, ‘What happens if the results come back flat? What are you going to do?’” You won’t always get clear signal from testing; other times, it won’t tell the full story, and tradeoffs will need to be weighed,” says Chou. “Push your team to take a position — a real hypothesis, not an apathetic one — and try to truly confirm or deny it. Experimentation shouldn’t be a tool to remove human judgement and pass the buck.”

Fostering intuition and self-sufficiency in your team takes patience; often it may be faster and easier to just make a call yourself and move on. Resist that urge. You’re teaching them to say, ‘This is the plan for what I’d like to do. This is the rationale. Do you have feedback on it?’”

Teach your team not to look to you for decisions all the time. That happens less through an explicit dialogue, and more across lots of small acts resisting the urge to make calls for them.

Goals

Once people internalize a sense of ownership over their work, they’ll need clear goals to hone their intuition and sustain motivation. And the best goals are measurable, hard to achieve, and impactful to the business. One way to quickly set those goals is to agree on a set of target metrics: measurements of the project, team or company’s progress. But be careful. Metrics can quickly go from motivating to frustrating if they aren’t calibrated to the product’s lifecycle.

Chou identifies three key stages of product development: invention, scaling and optimization. “As a company matures, you’re not just trying to build a thing that you’ve already built. You’re trying to build the next thing. But you’re also trying to make the thing you’ve already built more valuable. And at each of those stages, the goals you set — and the metrics you track — will be very different.”

- In the earliest stage of product development, metrics typically aren’t yet in play. “We have a team here that’s working on something that doesn’t yet exist in its form in the world,” says Chou. “We can't really look at the progress we’re making against a progress metric and goal. So we need some level of conviction and a bias to ship in small, confident chunks. Absent clear metric goals, teams in the invention stage will need to lean heavily on the fourth element of the pyramid, mission.”

- When you have something that works on a really small scale, but multiple X from making the impact you’d like to see, you’re scaling a product. Here, the metrics are front and center — but too often, Chou sees teams vastly undershooting. “You'd be shocked. Even seasoned product people in scaling mode will sometimes say, ‘Well, if this large complicated new thing is a home run, we’ll get a 5% lift.’ If that’s the case, you missed something,” says Chou. “At this stage, think in terms of changes that will have much larger impact if perfectly successful.”

- The optimization phase, on the other hand, is where small gains can add up in meaningful ways. “That’s where we do think there are maybe hundreds of 1% opportunities, and if you add up all those it makes a really big difference,” says Chou.

Once you understand where you are in the product lifecycle, metrics are a valuable tool for motivating and focusing a team. Chou frequently catches teams poring over metrics with no clear sense of what their target should be. Help them set the right goals, and you’ll also be guiding how they think about key business decisions.

“Take a team in scaling mode, for example. If they’ve never worked on improving something in the product, you might tell them, ‘I think a reasonable goal for that particular metric by end of year would be 5X. That’s not an aggressive stretch goal. I think that if it’s not five times this size, you probably shouldn’t care about,” says Chou. “Then the team can say, ‘Okay, we need to 5X this narrow number by end of year, as opposed to the 50% lift we were targeting. That’s a big difference. We need to switch tacks. The only way to do that is to think about bigger changes.’”

“There's almost nothing more clarifying than if you can tell a team, ‘Hey this is it. This is the target. You’re right. Go hit this,’” says Chou. “When you orient around a goal, you can also celebrate the right wins, another important way to keep teams aligned and enthusiastic. You want to be celebrating your impact. Not ‘Hey, we shipped this thing.’”

Goals, then, become a powerful way to offer guidance without compromising the team’s sense of ownership.

Mission

By the time you get to the top of the motivation pyramid, if everything is going well, you should have a team forged by chemistry and ownership over their work, that is also driven by clear goals and metrics. Now, to achieve lasting motivation, you need to ensure that they also understand how that work benefits the company as a whole.

Much like ownership is complicated by rapid growth, it’s more challenging to convey mission to 300 people than it is to five people sitting around a table. “Communication gets harder each time the organization grows,” says Chou. “As employees’ contexts and areas of focus diversify, it may be increasingly difficult to get everyone on the page. How you adjust to that becomes really important.”

Chou recommends two strategies: give teams the opportunity to share what they’re working on with the rest of the organization, and repeat your mission often (and in plenty of different mediums).

“When the company was 30 people you probably didn’t need to create formal communication structures. You may not have needed to create opportunities for folks to bring ideas forward to the broader group. As you grow, you have to do all that,” says Chou. “And people learn in different ways as well, right? So, you have to state your mission, your purpose, over and again but also in different ways from different voices. The best leadership teams that I've seen focus on communicating mission through every medium. Email. Rewards. All Hands presentations. Goals. All of them tie back to the mission explicitly. We spend a lot of time designing not only products, but how our team hears the mission. Take inventory of which forums and channels your people are hearing your mission. It should be at least once a week in email and once a week in-person.”

As time consuming as that may be, don’t shortcut this part. Ultimately, mission gives your pyramid height, making it a beacon for others within and beyond the company. Each of the other components of motivation is reinforced by a strong sense of mission: “Is everyone on your team here for this purpose? Are people working toward the same thing? Do they take ownership of product decisions? Do you understand the broader context of what you’re trying to do as a company? Can you look at your metrics and see how they translate into improving people’s lives?” says Chou. “Because at the end of the day, feeling like a part of something bigger is what gets people to the office every day.”

People want their work to be about something more than just making money for a Delaware corporation.

HOW TO SPOT FLAGGING MOTIVATION

Rapid growth is hectic. Companies change and break. Keeping all four levels of the pyramid strong is no small feat, and inevitably you’ll need to reinforce them from time to time. When a team starts to lose motivation, you’ll typically start to notice it through one of two channels:

- Output. “Are you seeing the output at the velocity that you would expect to see it?” says Chou. “If not, ask yourself why. If you have people who are good at their jobs in small dedicated teams that cover all the functions — and if they feel like owners and understand their goals and how they fit into the mission of the company — they’re going to move pretty fast,” says Chou. If a team is lagging, then, one of those essential components is likely missing. “I once observed a team moving really slowly. After digging into it with the team, I discovered that its members thought they’d been forced to work on the founder's pet project. It was the worst because they not only didn't see how it fit into the mission of the company, but also they felt no ownership of it. We spent three hours together tracing back to the original problem the founder was attempting to solve — and asking them how they’d solve it. The team ended up with a different solution, but it was as effective, and they felt like owners working on it.”

- Conversation. Other times, people may be telling you that they’re losing steam. But don’t wait for explicit announcements — you’re going to need to read between the lines. “There's a reason that being a manager is a really tough job: it’s all about human beings. So things sound very simple in a management book, but it’s actually a complex puzzle,” says Chou. “Each person is different and you really need to hear them out. Listen for simple warning phrases: ‘I don’t know why so-and-so is doing that.’ ‘We’re not quite on the same page about this.’ ‘We’re taking some time to decide this.’ Another red flag? A team member who stops asking questions, stops trying to figure out where their work fits in the bigger picture. In all those cases, it’s important to sit down and figure out how to unpack that, unpack it all the way.”

The easiest way to diagnose flagging motivation, then, is to create more opportunities for people to talk to you. Even simple changes to your team’s routine can open the door to candor. “I think it’s Andy Grove who said that one-on-ones should be 45 minutes instead of 30 minutes because all the interesting stuff happens at 25 or 30 minutes. The question you need to ask yourself is ‘What does this person want to tell me that they aren’t telling me?’ The way to find out is usually by sitting in a room long enough, just talking.”

And remember, candor is a two-way street. If you want to get the most authentic dialogue with your team, you need to give them something, too. “I try to be the most authentic person that I can be,” says Chou. “’This is what's going on in my life and this is what I care about and this is what gets me excited and this is what I don’t like.’ Then when I'm talking with people, I hope I'm getting pretty good signal from them, not just hearing what they think I want to hear.”

TURNING THINGS AROUND

When you do spot the signs of flagging motivation, act quickly to diagnose the source and take action. Chou shared a few common failure modes he’s seen across roles and companies, and advice for how leaders can turn motivation around.

1. Engineering feels like it works for Product teams, not with them. Chou has seen this one many times. While engineers may have enormous responsibility for building products across the platform, they don’t always feel ownership of the products and product decisions that are being made. “Product says, ‘Build X because we’re building Y’ without much context. The engineers don’t feel ownership over anything.”

The fix: Create that sense of ownership. Good Product people make sure their counterparts, including engineering, are true partners in understanding the problem and carving out the solution. And when a company gets large enough, Chou has had great success breaking up large technology teams into smaller ones and making that smaller team responsible for a clear scope and goal. That not only puts them closer to key decisions, it eliminates confusion about who is responsible for achieving the finished product. “You can try to tell 20 people that they should all feel like owners of something, but they’re not going to. They're looking around the room.”

2. Your product managers are in execution mode, but no one feels like they have a stake in making decisions. Sometimes, a PM or team might be very close to their metrics — well versed in what they need to hit and why — but still feel like product decisions inevitably come from above. They quickly get stuck in a rut, either feeling sorry for themselves or simply falling into the habit of abdicating responsibility for their product plan.

The fix: Force those leaders to make decisions. Be clear. “Say, ‘It's always within your rights as a product manager in any company to stand up and say what you think we should be doing and why,” says Chou. “Explicitly assign responsibility for key decisions. This morning a PM on my team was saying, ‘Gosh, I don’t know whose call this is.’ And I wasn’t sure yet either. But anytime I hear that, I just say, ‘What call would you make? Why don’t you try to make it to start. Then let’s talk about it.’”

Pushing responsibility to someone who’s demonstrably unmotivated can yield a couple of benefits. For starters, you may get a good solution to a problem that needed solving. Perhaps more importantly, though, you get that person back in the game, personally invested in where things are going and how the team gets there.

3. Leadership has moved on to setting and pursuing big goals — but a team’s interpersonal dynamics are still rocky. “I think every leader has fallen prey to this one,” says Chou. The company is moving fast and you’re eager to start digging into those metrics and product roadmaps. But “people” is the bottom of the pyramid for a reason. Until you solve their fundamental challenge, you’re unlikely to really hit your stride.

Getting to the bottom of a frustrated team is often tricky for founders and early executives, who are problem-solvers by nature. “Founders may think, ‘Problems come to me, I figure out the answer, and then the answer goes out. But the team problem is not one that can be solved by thinking hard and spinning up a solution,” says Chou. “Actually, it’s quite the opposite.”

The fix: If a team isn’t working well together, don’t exacerbate the problem by removing their sense of ownership, too. “Stop and listen to where people are coming from,” says Chou. “Do you understand why these people feel like the team is not properly resourced with people they trust, or who have had enough time to build a rapport?”

It’s easy to hypothesize what’s bothering someone. But until you ask, you’re unlikely to accurately diagnose what people really need. So simmer down your own opinions, ask open-ended questions, and then sit back and digest whatever you get back.

4. You’ve been focusing on a particular metric for a while, but it’s no longer the right measurement for what you’re trying to accomplish. Products evolve, and the metrics that made sense for one iteration may not be as valuable for the next. Affirm, for example recently reevaluated their key metrics. “We’ve started to turn our sights toward really improving people’s lives. If a smaller number of people are financing a lot of their spending with Affirm, that’s great, but we’re trying to impact a large population of customers,” says Chou. “So we asked ourselves: are we measuring that? Are we focused on that?”

The fix: Keep talking about your goals and your metrics, as a company and as a leadership team. Continue to ask if what you’ve been tracking still best represents the product you’re building. Sometimes the answer will be yes, and you’ll benefit from the recommitment. Other times, you’ll decide to recalibrate, and clarify your direction in the process. Teams can accomplish this by setting default cadences to review metrics and goals. At Affirm we do it quarterly — heavier at mid year and end of year, lighter at start of Q2 and Q4. Each team shares their metrics and goals from first principles each time to make sure they're thinking about it originally each time. We recently changed our primary User metric to better fit how our business has changed.”

Remember, metrics are more than just figures on a page. They lead to your goals. And once goals become muddy, it won’t be long before teams lose their focus and motivation, too.“ A healthy company uses metrics at many different levels in the organization. They need to end up being coherent when explained together,” says Chou. “But the most important thing is that they should reflect what you’re trying to accomplish. The moment you try to achieve something even slightly different, it’s likely the metrics should change as well.”

BRINGING IT ALL TOGETHER

The elements of motivation — people, ownership, metrics, and mission and purpose — are not only individual drivers that galvanize and energize teams, but all the more powerful when sequenced and stacked on each other. That’s why Chou visualizes these components as a pyramid, where chemistry between people is a precursor to a feeling of ownership, which is a prerequisite for effective measurement and metrics. For a motivation that brings employee longevity, teams must level up to an unwavering mission and purpose. All of these drivers become harder to reach and sustain as a company scales. That’s why Chou calls out two places were motivation can slip, as well as how to right the ship in common, tense scenarios.

“Once a team can say, ‘Yeah, I like working with these people. I get to make decisions that are pertinent to what I'm doing, we’re hitting our numbers, and I understand why these numbers translate to what we’re trying to do as a company over 5 to 10 years,’ then people really have a clear and motivating path,” says Chou. “And when they do? You’ll quickly learn to spot that, too. Output will flow. Targets may even be exceeded. And, perhaps counterintuitively, you’ll probably start to hear more arguments and impassioned discussions. Usually if folks are having a healthy debate, you’re in a good place. Because if they weren't engaged or motivated, they wouldn’t care to have those conversations in the first place.”

Photography by John Fedele/Blend Images/Getty Images.