Kim Scott had one thing to do that day. She was going to price her product. It was the year 2000, she was the founder and CEO of Juice Software, and she had blocked off her whole morning to make this decision.

The moment she stepped off the elevator, she was met by co-worker after co-worker who needed and wanted to talk to her — one about a health concern, another about his kid excelling at school, another about a disintegrating marriage. She comforted, celebrated with, and listened to each one in turn. She didn’t, however, price the product.

“For a minute I thought, this is where the assholes really have the advantage,” says Scott. “But that’s not right either. Good managers give a damn.”

This is just one piece of advice Scott discovered during the last 20 years, and has carried with her through leadership roles at some of the biggest and influential tech companies in the world. Most recently, she advised Dropbox and Twitter. At First Round’s recent CEO Summit, she shared what she believes to be the most important management lessons she’s learned.

WHAT IT MEANS TO GIVE A DAMN

“The most surprising thing about becoming a manager is all the pressure to stop caring,” says Scott — and she doesn’t mean caring about the work, she means caring about the people. “I was excited about the product and the opportunity [at Juice], but also I was excited to build a team of people who really cared about each other and loved to work together.”

The morning she got distracted from the pricing decision was not an exception. Finding the time to focus on “the work” without being interrupted was a constant struggle. She even called her CEO coach at the time and asked, “Is my job to build a great product or am I really just an armchair psychiatrist?” She got her answer when her coach literally yelled at her: “It’s called management and it is your job!” “These words have always rung in my ears, every time I’ve been tempted to stop caring,” Scott says.

Management is a deeply, deeply personal thing.

“You have to be a human being. Some people think being caring and empathetic is a personality trait — but it can be learned. Especially when you’re hiring a lot of college grads, these people are talented and they’ll grow fast in their careers. You need to take time to teach it to them.”

Good management is about deep personal relationships, which can be hard to accept when you’re all about growing fast. As Scott says, the hardest lesson about giving a damn — about management — may be that it doesn’t scale. And that’s okay.

The Tactics:

“The simplest tactic around giving a damn is to push your managers to have career conversations with their people,” she says. “This isn’t about mapping out their path to promotion, it’s about really getting to know them as human beings.” And it’s actually two conversations:

- Their past. What changes have they made over time? Take their history as they tell it to you and pull out their core values, what motivates them, what do they really care about? Write down three to five learnings and then verify them with the person: “So what I’m hearing you say is that you care about freedom — freedom of time, not the freedom that money buys. Am I right?” Make sure you understand them, Scott advises.

- Their future. “Ask them: What are the three to five things they really want to be? Nobody knows the one thing they want to be — but they’ll probably have three to five conflicting images of what they really want to do in life.” Get those on the table, and encourage the person to be honest. Have fun talking about it.

“One person I talked to told me he really wanted to run a ranch,” Scott says. “Another wanted to spend eight hours a day riding his mountain bike. You may never know these things about your people unless you ask. And if you ask, you can figure out how their goals and values — freedom, hard work, learning, whatever — can connect to the work you want them to do over the next 18 months.”

CRUEL EMPATHY

“There’s a Russian anecdote about a man who loved his dog so much that when the vet told him he needed to cut the dog’s tail off he couldn’t do it all at once, so he did it an inch at a time. Don’t be that kind of manager.”

Giving unclear, infrequent feedback has somewhat of the same effect — though slightly less violent. You end up hurting the person receiving the feedback more, even though you’re just doing what your parents always told you empathetic people do: If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say it at all.

This is where Scott says she’s seen managers make the most mistakes. “No one sets out to be unclear in their feedback, but somewhere along the line things change. You’re worried about hurting the person’s feelings so you hold back. Then, when they don’t improve because you haven’t told them they are doing something wrong, you wind up firing them. Not so nice after all…”

In order to give people the feedback they need to get better, you can’t give a damn about whether they like you or not. “Giving feedback is very emotional. Sometimes you get yelled at. Sometimes you get tears. These are hard, hard conversations.”

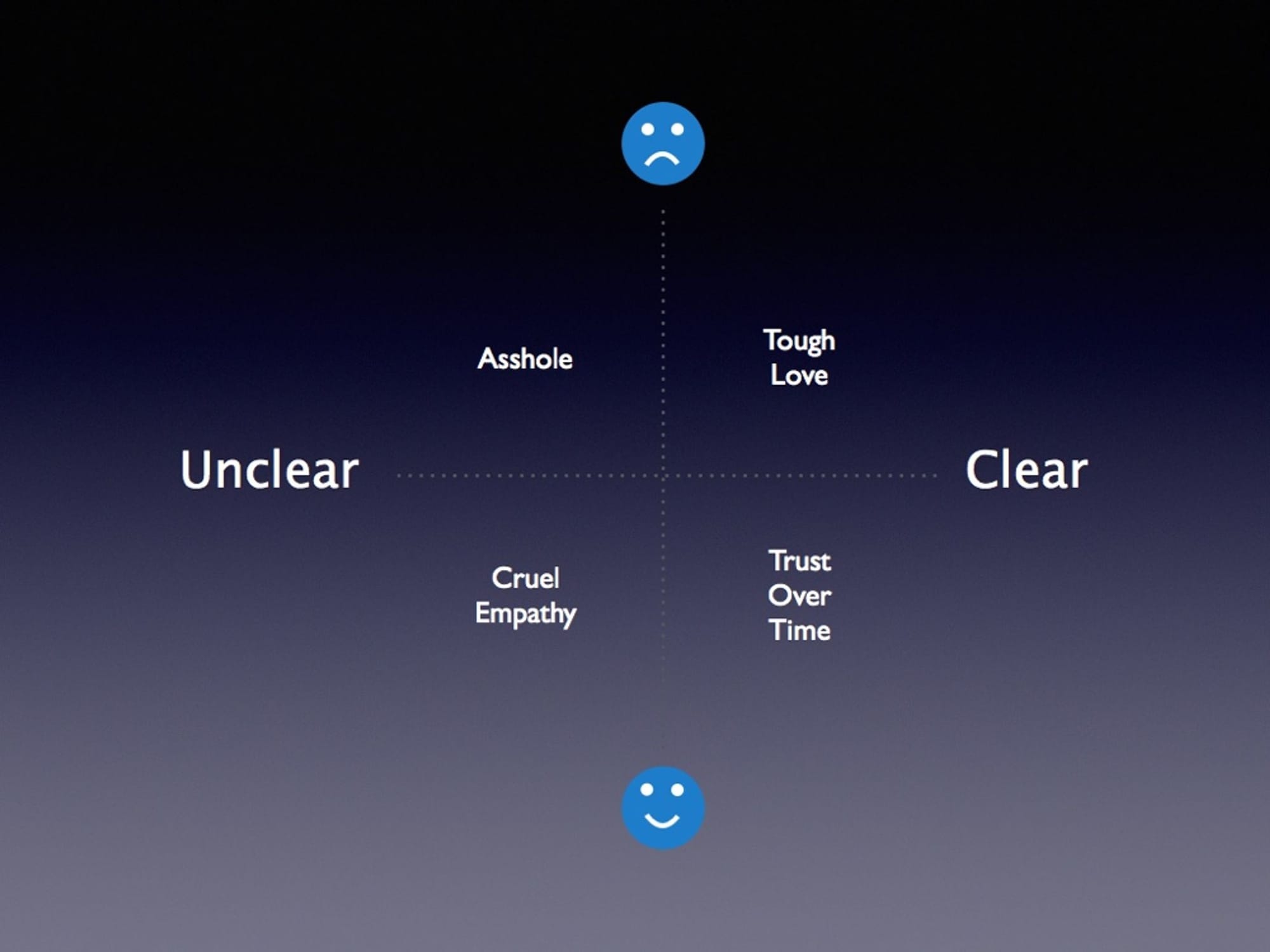

Scott breaks giving feedback into four quadrants. On the horizontal axis you have unclear to clear feedback, and on the vertical you have the spectrum of anticipated emotions from happy to unhappy. The gentler the feedback, the less clear it tends to be. That’s the cruel empathy quadrant. The one you want to be in is the top right — clear even if it’s bad news.

Tough love is how you build trust the fastest.

“When you’re hard on someone but they really hear you, that’s when you build trust over time,” she says. “They’re going to react emotionally. All you can do is react empathetically. Don’t try to prevent or control someone’s feelings.”

The Tactics:

- Just say it. “A lot of management training ties you in knots trying to say things just right. Just let it go. Just say it. It will probably be fine. Say it in private and say it right away. Criticism has a half-life. The longer you wait the worse the situation gets.”

- Don’t be loose with praise. Managers tend to expect that praise is easier than criticism, but it can go awry. “If you’re wrong about what you’re praising someone for; if you don’t know the details; if you’re not sincere; it’s actually going to be worse for the person than saying nothing. Praise in public, but only if you know you’re absolutely right and you mean it. Otherwise people will see right through you.”

As a manager, it’s also critical that you solicit feedback. But this isn’t as easy as it sounds. A lot of managers simply forget to ask. And very few people want to or will offer truthful feedback to their managers. Scott has some recommendations for this too:

- Reserve a special one-on-one every quarter with each of your reports. Warn them that this is the meeting where they give you feedback. Then make it easy for them to start the conversation. Ask them: “What can I start doing? What should I stop doing? What should I keep doing?” Whatever it is, come up with a formula that makes it easier to get the ball rolling at the start.

- Embrace the discomfort. To get people to open up, you have to make them uncomfortable, otherwise they’ll say you’re doing great and will try to move on. “Try just sitting there silently. Figure out a way to make it impossible for people not to tell you what they really think, because if they can get out of telling you what you’re doing wrong, they will.”

- Reward the truth. “If someone working for you has found the courage to tell you what they really think, honor that.” Scott once got a complaint that she was always interrupting one of her reports in meetings. She knew this to be true, but also knew it was not something she could change overnight — she’d been told since she was a child that she interrupted people. “I wanted him to know I wasn’t ignoring his feedback, so I started wearing a rubber band around my wrist and told him, ‘Every time I interrupt you, snap the rubber band.’ We had the kind of relationship where he happily snapped it, and it helped. Even though I didn’t stop interrupting immediately he knew I’d heard him, I cared, and I was willing to take action.”

PROVIDE DIRECTION

“The biggest thing I’ve learned about providing direction is that you do it with your ears and not your mouth,” Scott says. “The biggest mistake I’ve made and seen other managers make is that we’ll walk into a meeting with the team and say, ‘Here’s what we’re doing this quarter, or this year,’ and people are like, ‘No, that’s not what we should be doing.’ It turns out we haven’t listened to what people want and think we should do.”

So, first you have to listen.

Next, you have to decide. To make sure everyone’s voice is heard, you need a cycle of debate and clarification. “Debate and clarify, debate and clarify,” Scott says. “This can feel tedious and political, but you have to go through it to get to the right decision. Teach this to your team of managers so that no one ever goes into a room again saying, ‘Here’s what we’re doing,’ without going through this cycle.”

Then you have to communicate. "But don’t spend too much time communicating because if you’re a great communicator, people will start to tell you where they disagree, and it’s time to start listening all over again..."

The Tactics:

The Big Decision Meeting. Scott created this after recognizing all the angst around her staff meetings. Everyone wanted to be included because they felt like big decisions were getting made there, but this was hardly ever the case. “Make fewer decisions in your staff meeting and create a second meeting explicitly to deal with important decisions,” she says. “Delegate these decisions to people who are closer to the information.”

Consider using your staff meeting to set the agenda for the big decision meeting. Identify the three most important decisions that need to get made that week, and who should make those decisions. Who is closest to the work involved? “This is how you push decision-making into the facts,” she says.

Citing James March’s book A Primer on Decision Making, she recommends that managers exclude themselves from big decisions as much as possible. “Somehow people’s egos get invested in making decisions,” Scott says. “If they get left out, they feel almost a loss of personhood. So you get ego-based decisions instead of fact-based decisions. The more you push yourself and your managers out of the process, the better your decisions will be.”

Most of all, don’t let decisions get pushed up. “A lot of times you see decisions get kicked up to the more senior level, and so they get made by people who happen to be sitting around a certain table, not the people who know the facts. Don’t let this happen.”

Use meetings with reports to invest them in the company’s direction. In one-on-ones, let your employees set the agenda. “Don’t let it just be an update — they could email you that. Instead, ask and then listen: What do they want to be doing? What are they not doing? What do they feel like they ought to be doing?”

Block off a whole hour for each report every week. You don’t have to fill the time, but they should know it’s there if they need or want to. Try to have the meeting over a meal, or in a more casual setting. “This is why it’s important to limit reports to five to seven per manager. This type of time and attention doesn’t scale,” Scott says.

If you're going to be a great manager, you can't have too many reports.

Outside of one-on-ones, set a quarterly meeting with absolutely no agenda with each person you manage, she recommends. “Take a walk or grab a drink. Just talk about life. This is where you will learn the important things.”

TAILOR YOUR LEADERSHIP

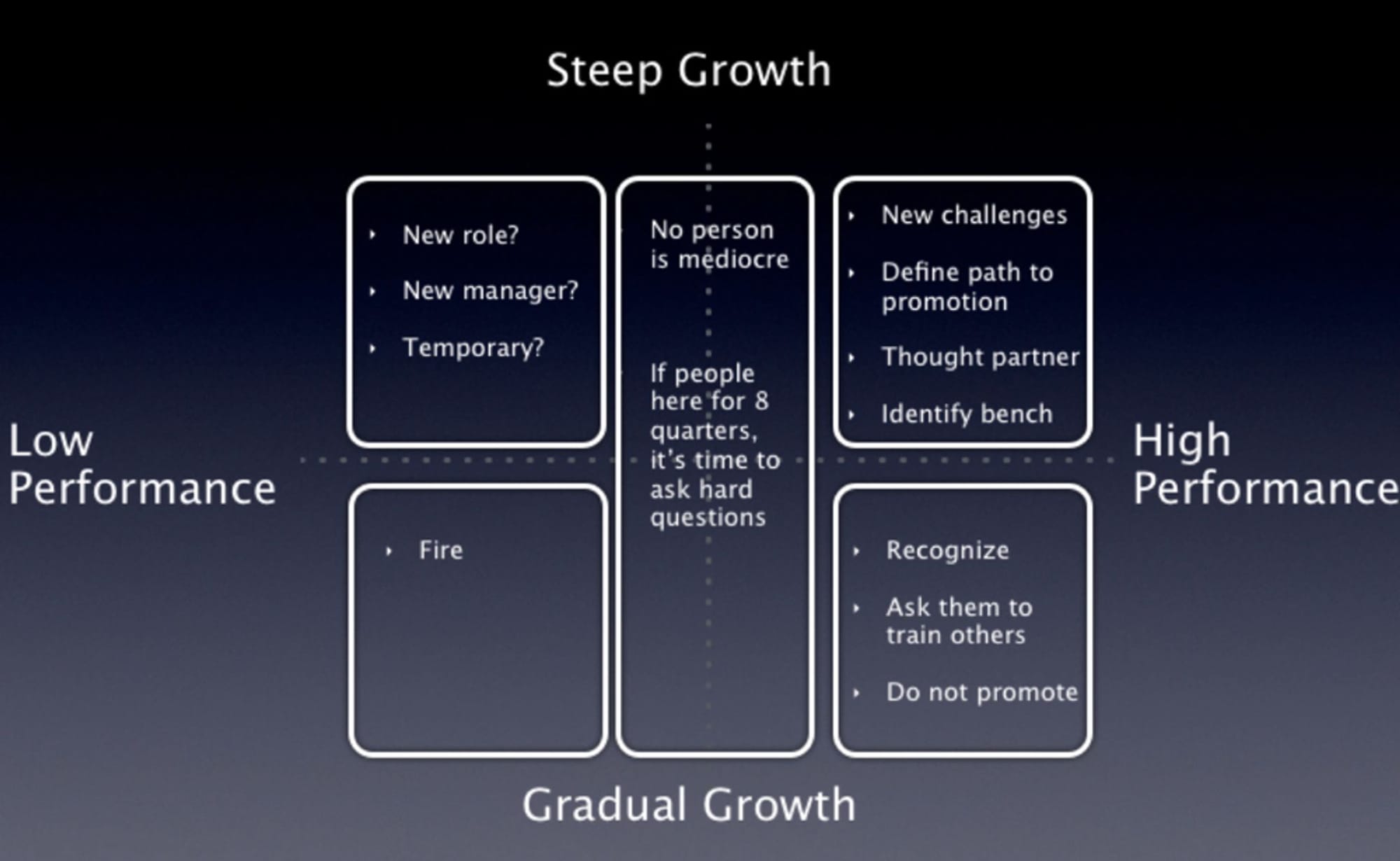

In the book The Fountainhead, there are two characters: The architect who is destined to change the face of the city, and his best friend, the electrician — the unsung hero who brings the city to life. To Scott, they are representative of the two major types of high-performing employees: People on a steep growth trajectory, and people on a more gradual growth trajectory.

“At too many companies, people on a gradual growth trajectory are treated as second-class citizens. This is a mistake,” she says.

People on a steep growth trajectory need to be managed in a very particular way. “You need to make sure you’re pushing them to take on new challenges. Make sure you are defining their path to promotion. Make them your thought partner. Don’t ignore them because they are independent. Don’t ignore them in the spirit of not wanting to micromanage them.” At the same time, these employees can be high-maintenance. They are unlikely to stay in one place for long.

“The people on the more gradual growth trajectory, they are the ones who will be in a role for a while,” Scott says. “You have to honor them for the great work they do, because too often they go unrecognized.”

The Tactics:

- Give excellent ratings to everyone who is performing exceptionally. Even at some of the best companies, people who have valuable skills but who aren’t likely to “take over the world,” will often be rated as meeting expectations because managers reserve high ratings for people they're going to promote. This creates an unhealthy promotion-obsessed culture.

- Put the gradual growth achievers in positions where they can train others. Capitalize on their dependency, their thoroughness, and their dedication to the company. They will be your best teachers, and it’s a way to put them on stage even when they shy away from the spotlight. “Don’t promote them,” Scott advises. “They don’t want to be promoted. If you make them a manager, you’ll destroy an asset.”

- Don’t ignore the middle. Very few people are truly mediocre. “If someone has been somewhere more than two years and has just met expectations the whole time, it’s time to ask yourself the hard question: If they weren’t there could you hire somebody more likely to excel?

- Evaluate skilled underperformers. If somebody is not doing well in their role but is talented, it’s time to look at yourself in the mirror: Have you put this person in the wrong role? Is your management style just a bad fit for the person? Is this person experiencing a temporary personal problem?

- Make the tough calls. If someone truly is bad at their job and they are unlikely ever to improve — that’s key — you have to fire them. “Don’t put it off. All that’s going to do is piss off your top performers and burn them out,” Scott says. “It may seem harsh, but it’s also harsh to let your top performers carry the burden for underperformers.”

Require all of your managers to take 15 minutes to slot their reports into one of the five boxes in the matrix above. Have them literally write the names in the quadrants, and have them do this once a year. Urge them to take action on the results.

“Make sure you’re doing right by every person in every quadrant,” Scott says.